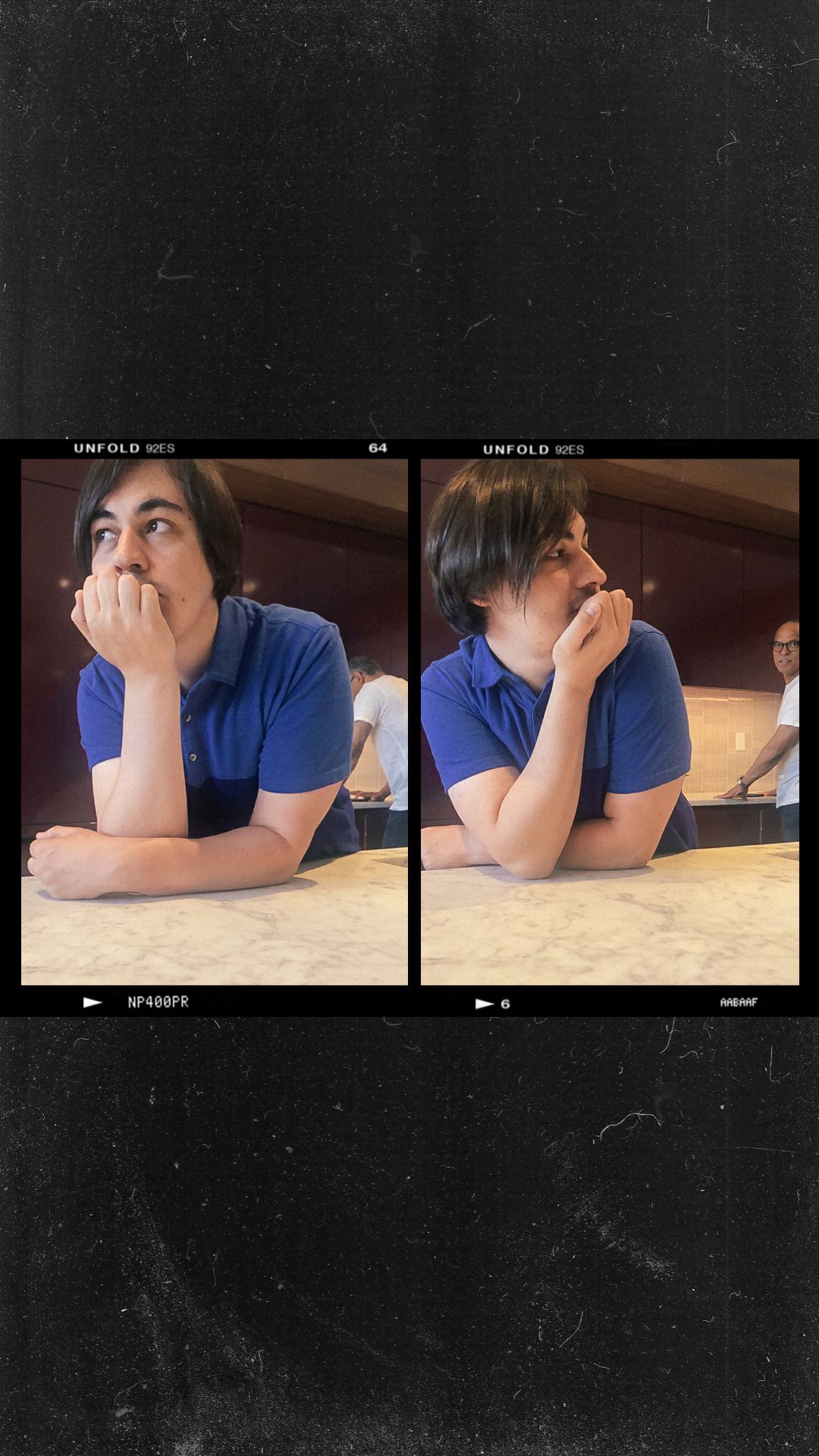

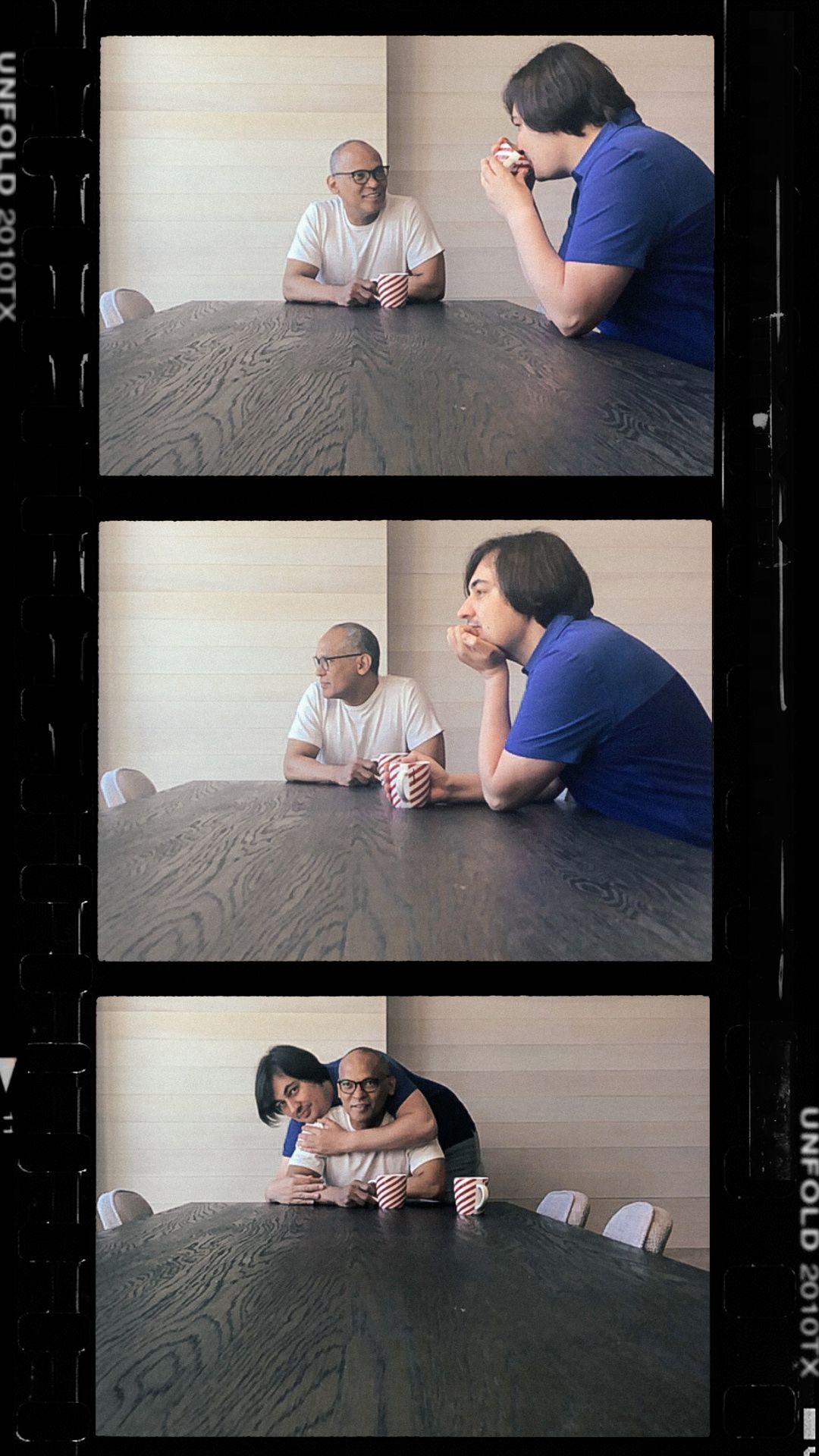

Dmytro and Phillip

Despite his love for the country where he was born and raised, Dmytro Pichakhchi refuses even to think about returning home. Only after moving to the United States, he finally felt safe and began living a full life in which there was no room for hatred.

If I don’t leave, I will die

In Kyiv, feelings of hopelessness and physical threat constantly plagued me. When I went to a store or a cafe, I was trying to assess the potential danger: who was there, how they looked at you, what to expect. One day I went on a date with a guy to the cinema, the people who were there asked, “Are you gay? We are going to make sure that you do not kiss”. After 2015 Pride, I started receiving threatening text messages. A group of ultranationalists got my picture; my friends and I were hiding as we were afraid of violence. The feeling of constant fear paralyzes, you turn into a vegetable and cannot live normally. I read stories about the beating of LGBT people and realized that it was only a matter of time before they would come after me. On the one hand, we had a Revolution of Dignity, people woke up, started going abroad, and see other behavior patterns, but little has changed in Ukraine. I understood: if I don't leave, I will die.

I have only one fear — to come back to Ukraine.

When the Pride ended, my boyfriend and I took the tickets and flew to visit a friend who lived in New York. We planned to have a rest for two weeks, take a break, exhale. However, when the vacation came to an end, I felt that I did not want to return. I no longer had the strength to live in constant fear and tension. We found a pro bono lawyer who helped to properly apply for political asylum (in the United States, law firms have to work a certain number of hours helping for free). It's been five years, I haven't had an interview yet - the lines are so long - but I was given a work permit six months later.

When I left Ukraine, I had a million fears. At the moment I have only one - to go back.

Activism in the USA

Many times on Ukrainian gay forums I saw statements that we should sit quietly and not show up, then we will not have any problems. It’s hard for me to understand because living underground is a sad prospect. I participated in the Kyiv Pride and continue to do so in the United States, although there is a difference in the philosophy of the event in these two countries. In the States, it is a celebration of visibility and security. People (sometimes very different) come together to show: we exist, we are together, we fought for our rights and we won. In the New York Pride, there is a column of the city administration, a column of firefighters, police. It shows that we are all one society, and there is no difference between us. Going to the streets, the American LGBT community notes the fact that it once ceased to tolerate violence and bullying, took the path of fighting and successfully went through it. Pride in Ukraine is a march for rights that people do not have yet. The event is organized by only a few courageous activists, as society is not yet ready to unite and openly demand equality. In my first year in the United States, I was in a column of immigrants from post-Soviet countries, mostly Russia. However, it was difficult to find common language with them. Even though these people fled because of the policy of hatred and persecution, they supported the imperial rhetoric and were not ready to treat Ukrainians with respect. I felt uncomfortable going under the Russian flag and talking to people who respect Putin and consider Crimea part of Russia. I love Ukraine, I wish it well, and I left not because I wanted to, but because I had no other choice. By the way, the conflict with Russian-speaking LGBT people helped me integrate into American society more quickly, despite my terrible English.

For the next two years, I went to Pride with other columns - international and under the auspices of the human rights organization Amnesty International. Until 2019, we organized a separate Ukrainian-Georgian column, uniting immigrants from those countries that did not want to be under the Russian tricolor.

Returning to the comparison of Ukrainian and American Prides, I want to share a small episode. It’s 2016, summer, heat, long event. I see a priest and nuns coming out of the church nearby. My heart was about to burst, I was thinking to myself: well, it’s all starting now. But they did not utter curses and call for repentance. The women took out water and gave it to the participants of the pride, and the priest held a garbage bag for used plastic cups.

My second mother

As an activist and openly gay, I did not have a warm relationship with my family. They treated me like I was mentally ill and just put up with me. My father and I did not speak for ten years; he only called before he died and talked to me for a minute. I was not close to my mother, either. She only supported me when I told her on the phone that I was staying in the United States. She said that this was the right decision because, in Ukraine, we live like in a swamp, so maybe I will build a normal life in the US. My brother thought I was a disgrace to my family: only 15 years after my coming out, we learned to communicate with each other. I have never known what care and love are, from childhood, I was on my own.

But being an adult, I met a person who became my second mother. Her name is Anna Georgiivna, but I call her mother Anya. She is the mother of my close friend, whose place I lived for some time in Kyiv. Thanks to this bright woman, I understood what faith and support were without a shadow of judgment. I remember once I went to a nightclub, and suddenly mom Anya called and asked if everything was fine with me because she was worried. Then, at the age of 19, for the first time in my life, I felt what it was like when someone cared about you. Now we chat with her 2-3 times a week. Last year, she came to visit me in New York, and together we walked in a column at the pride. I told everyone that she was my mother because I consider her my mother.

Anna Georgiivna became one of the co-founders of the Ukrainian public organization TERGO for parents and relatives of LGBT children. It’s hard to believe, but some activists said she had no right to be a member of the LGBT movement because she didn’t have a gay son. However, this woman “adopted” someone’s child and loved him as her son. Is there anything more beautiful?

Healing love

When I came to America, I was completely disoriented. Unfortunately, my boyfriend and I were not ready for the new reality as a couple, so we decided to end our relationship. However, three months later, I met Philip, a man I am still together with. We met in the street, but the irony is that at that time I did not speak English at all. We talked using gestures: he texted me and I google translated his messages, he shared his coordinates on the map so that I could come on a date. I used charades trying to explain words I didn’t know. One day we were sitting together, and I said to Philip, “You don't understand me.” He replied, “I don't understand, but it doesn't matter because I love you.”

Philip is 20 years older than me, but I don’t feel the age difference. The only thing that sets us apart is the way we grew up and lived because it formed different worldviews. Philip was born into a family where parents supported their children, respected their personalities, and encouraged them to find their way. He is wise, balanced, and teaches me to look at the world differently. I have always considered myself open to any human manifestations because I am an LGBT activist, but thanks to Philip I saw how far from the truth I was. I could point to a woman who I thought was dressed silly or complain out loud about an impolite waitress. Philip was calmly explaining that people should not be judged; they should be treated with understanding and respect under any circumstances. Maybe the waitress just had a bad day, and instead of arguing, I should smile and try to cheer her up.

After meeting Philip, I realized that we are all traumatized in Ukraine. It’s not so much about sexual orientation, but more about constant guilt complex that has been instilled in us since childhood. He asks me, “Why are Ukrainians always showing their care through violence?” And this is true because when I shout that I will not let him out without a jacket, because it is cold over there, I show my love this way. Fortunately, Philip knows this and patiently teaches me other behavioral scenarios. My mother Anya is happy for me, and she keeps asking how Philipchik is doing. When she came to visit us, she always tried to feed him something tasty. I’ve never been jealous before, and now I feel something like jealousy, jokingly, of course. I could have never imagined that my mom would care about my boyfriend’s feelings. I am a very happy person.

Text by:

Maria Zhubreva

Photo by:

Arthur Aleksanian

We seek to assist Ukrainian LGBTQ + individuals living in the US and Canada to integrate, adapt, and productively contribute to American society.

Anna Konde

Балтімор, США

Pavlo and Brian

Los Angeles, CA

Aleksandr Smirnov

New York

Tanya Mazur

Washington, D.C.

Svitlana Zemlyana

Novi Sanzhary, Ukraine

Dmytro and Ronaldo

New York, USA

Viktor “Frenchman” Pylypenko

Kyev, Ukraine

Dmytro and Rob

New York, USA

Lyosha Gorshkov

Pittsburgh, USA

Damien and Dmytro

Chicago, USA

Roman and Anton

Атланта, США

Bogdan Globa

Washington, D.C.

Viachaslau and Shawn

Washington, D.C.